Despite the high profile campaigns, petitions and hashtags, this month BBC Three is set to go off air and become online-only. Although the decision to move BBC Three branded content to the iPlayer will reportedly make savings of around £30 million a year, the BBC Trust acknowledged that ‘almost 1 million younger viewers could desert the corporation as a consequence’.

With young people spending more time online than watching television for the first time ever, changing consumption habits seem to provide a strong rationale behind BBC Three’s departure from the linear broadcasting landscape. However, when asked back in 2014 to comment on what the axing of BBC Three as an on-air channels means for the future of other niche services such as BBC Four, former controller, Danny Cohen stated that “if future funding for the BBC comes under more threat then the likelihood is we would have to take more services along the same [online only] route [as BBC3].”

More recently, concerns around the future of BBC Four and other key platforms for specialist arts and cultural content were raised after a speech by Tony Hall in September of last year in which he stated:

“In summary the BBC faces a very tough financial challenge. So we will have to manage our resources ever more carefully and prioritise what we believe the BBC should offer. We will inevitably have to either close or reduce some services.”

In my own research interviews with media professionals and those who work within arts organisations in the UK, the possibility of more arts content being distributed online as opposed to traditional broadcasting has been met by both enthusiasm and concern in equal measure.

In theory you might expect that having more arts content online would encourage what many would argue is a much needed increase in diversity in terms of both form and content.

Online platforms allow for a wider variety of ways to create and consume content, such as articles, vlogs, images, along with more traditional long-form video including documentaries and live relays. Further to this, commissioning online content tends to involve less risk as the costs involved both in production and distribution is generally less than that of traditional broadcasting. Of course even further reduced budgets is not good news for those creating the content and in turn may lead to fewer producers specialising in the arts, particularly within the independent sector.

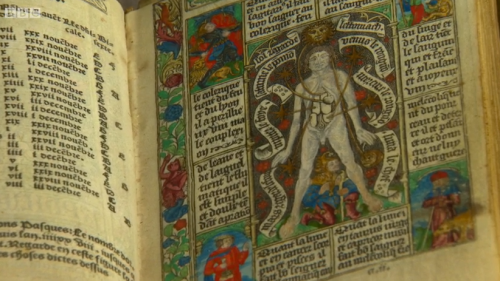

Another advantage to online platforms is that they are not constrained to the comparatively limited space of radio and television schedules, enabling a potential increase in the amount of arts coverage available. Along with this, the internet allows for a more immediate reaction to events than traditional media. You can be watching an interview with a curator at the opening of their new exhibition just hours after it opens before switching to a livestream of an opera direct from Covent Garden.

In line with the BBC Three model, being able to access more content online and on demand is also about responding to changing media consumption habits, particularly those of young people. The audience for linear broadcast television is ageing and this trend is even more concentrated in the arts.

So could online arts provision be the solution? In 2014 the BBC launched Private View, a series of iPlayer exclusives with a younger demographic in mind. The films consist of prominent figures from pop culture such as musician Tinie Tempah and fashion icon Lianne La Havas taking the viewer on a ‘series of personal tours of blockbuster exhibitions’. The series has proved something of an online success with Goldie’s Private View of Matisse being the most watched arts programme on iPlayer.

However, there are concerns around whether arts broadcasting could actually suffer more than other genres in this more fragmented, menu-based system. Back in the days when you had perhaps only three television channels to choose from you might watch an arts programme just because it happened to be the next thing on. Even now, decades after the Reithian diet of ‘lowbrow’ and ‘highbrow’ programming sitting alongside each other in the schedules has been rendered obsolete by digitalisation, you might still see a trailer for an arts documentary that catches your interest at the end of Eastenders.

There’s no escaping the fact that the core audience for arts programming is small, and while online platforms may be great for ‘binge watching’ the latest hit drama, there seems to be little opportunity in this user-led environment for broader audiences to be introduced to new content and ideas.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly for public service broadcasters, if the resurgence of event television in recent years tells us anything it’s that there is still nothing like the impact of mainstream broadcasting. Social media and live-tweeting have in many ways strengthened traditional media by making programmes talking points for live online discussion. Advances in media technology may mean that people are consuming more content online and on demand than ever before, but linear broadcasting still has an important role to play in creating a sense of shared experience and engaging people in a national conversation of which the arts must surely be a part.